In python, operator overloading means giving an extended meaning to an operator beyond its native meaning. An example that comes to mind is the + operator. You must have noticed that it has several meaning depending on the type of its operands. If the operands are ints or floats, like in ‘2+3’ then the + operator means add both ints together, but if the operands are strings like in ‘dog’+’cat’ then + operator means to concatenate both strings together. You can also use the + operator on lists or any other sequence type. This is what operator overloading is all about. Now, would it not be nice if we can carry out this same functionality on our newly created classes? So, python has created dunder methods that make operator overloading possible on newly created classes and not only on built-in data types.

Dunder methods (the full name is double underscore) are a set of methods that have a double underscore preceding the name and a double underscore after the name. If you read my post on OOP in classes and objects, you must have seen it when I implemented one with the __init__() method. Some people prefer to call dunder methods special methods or magic methods. These set of methods enable you to enrich your newly created classes so that they can emulate the behavior of the built-in data types.

Would it not be nice to be able to create a class that would emulate all the fancy methods of the list class, or even the string class? That would make your new class not only more flexible but a very interesting object.

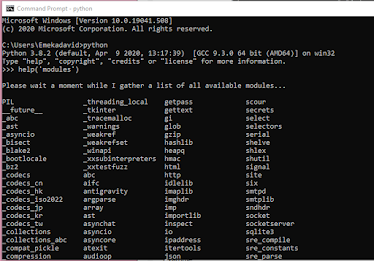

Below is a list of some dunder methods in the python data model. I will be implementing them with examples. If you want the complete list, you can consult the python data model reference.

| Common Syntax |

Dunder or Special Method Forms |

| a + b |

a.__add__(b); RHS: b.__radd__(a) |

| a - b |

a.__sub__(b); RHS: b.__rsub__(a) |

| a / b |

a.__truediv__(b); RHS: b.__rtruediv__(a) |

| v in a |

a.__contains__(v) |

| iter(a) |

a.__iter__() |

| next(a) |

a.__next__() |

| str(a) |

a.__str__() |

To illustrate the table above before we begin creating example classes, let’s take for example the + operator and its dunder method, __add__(). Imagine you created a new class and you want to be able to add attributes of the class together. If you do not implement the __add__() dunder method or special method, python will raise an error. But the moment you implement the __add__() method, whenever python sees a statement like a + b where a and b are instances of the new class, it will then search for a definition of the dunder method, __add__(), and when it finds it, it implements it. Python gives deference to the object on the left side of the operator such that when it is looking for the definition, it first operates like a call of the form a.__add__(b) where a becomes the calling object and b becomes the parameter. Where object a doesn’t have an __add__() method, it then looks to the right side of the operator, at object b, to see whether b has the special method by using the alternative form, b.__radd__(a). Notice the difference in the names for the left hand side call and the right hand side call. When the right hand side call doesn’t implement the dunder method, python will then throw an error.

This special way of calling dunder methods makes it so that even where the right side and left side operands are different objects, provided they implement the dunder method for that operator, the operation can be executed. This distinction between __add__() and __radd__() makes it possible that where an operation for a class is non-commutative, it can be executed.

As you can see from the list I provided above, special or dunder methods are not restricted to operator overloading. There are special functions that are built-in to the native data types that we want our new classes to emulate. Like for example, the ability of our new classes to behave like sequences, or to have string representations. Dunder methods exists for that. For example, given the statement, str(a), which is a string representation of object a, new classes cannot automatically implement this behavior but the dunder method, __str__() when implemented will enable new classes to emulate string representation. Also, remember that an object can be an iterable if it implements the __iter__() method such that it can participate in for loops.

In order not to burden you with explanations, I will illustrate all the above with example classes: a Student and Grades class. A student object is simply an identity for a student with a collection of grades. The list data structure is used to hold this collection. A grade object is just a grade that is an underlying int. In our Grades instance objects, we want to be able to add two grade objects, and divide two grade objects when looking for the average grade. We also want to have a string representation of grades so it can be printed. For a student object, we want the student object to act like an iterator so it can participate in for loops, we want a means of printing out the contents of the grades list of any student and also be able to run the ‘in’ operator on a student to find out if a grade is in the list of grades. Instances of the student and grade objects cannot do this unless we implement the dunder methods for them.

So, using examples, we will show how to implement all the desired behavior for the grades and student objects. But first I will like you to see how the Student and Grades classes were defined here.

You can download the class definitions here if you desire an in-depth look, student_grade.py.

Following is a concise explanation of the several operator overloading we are doing and the dunder methods that were implemented.

1. Overloading the + operator using dunder method, __add__()

To be able to add grades together for a student so that we can get the sum of that student’s grades, we need to overload the + operator. We do this using __add__() dunder method, or special method. In the Student class, I defined a sum_of_grades() method that accumulates all the grades for a student and when adding grades together it calls the dunder method of the Grades class.

The __add_() dunder method (lines 56-57) just takes the grades of two grade objects and sums them up and returns the sum. Just that. In the sum_of_grades() method, lines 35-42, we create a total variable that is also a grade object which is used to accumulate the values. This method, after adding the grades together, returns the total grades.

With this example, I believe that now you should have a basic understanding of how operator overloading and dunder methods are implemented.

Let’s take more examples.

2. Overloading the division operator, /, with the __truediv__() dunder method

Another operation we want to perform on the student grades is to get the average grade after summing them up. That requires a division operation. Now to be able to do this in our grade objects, we need to overload the division operator, /, using the dunder method __true__div().

Let’s take an example. Run the code below to see how it goes.

One code that makes this possible is the implementation of __truediv__() method in lines 59-61. Where we just return the division of two grades. Then in the Student class definition, the method, average_grade, while doing the actual division, calls on the dunder method when a grade object is the numerator and another grade object is the denominator.

3. Dunder method, __str__() for string representation of objects

In order to carry out string representation of our grade and student objects, we have to implement __str__() dunder method. This makes it possible that we can print out to the screen grade objects or student objects. When print is called on a student or grade object, it casts the object to a string using str(object) and then this casting looks for the dunder method associated with the object. That is why we needed to implement this dunder method in our objects.

Let’s give an example of how this was done in the code. First, I will print out one grade object and another student object.

If you look at the last two lines in the driver code, we called print on math_grade, a Grades object, and also on michael, a Student instance. Print then called their dunder method and printed out what was implemented in the dunder method. Lines 44-45 is the implementation of the dunder method for Student instance objects while lines 63-64 is the implementation of the dunder method for Grades instance objects.

4. Dunder method to make the Student instance objects iterators

In my post on iterators, I made you to understand that for an object to be an iterator (that is act like a container that gives out its values when needed), it needs to implement the __next__() and __iter__() dunder methods. Any object that implements these two methods can participate in for loops, and can be treated like iterables because all iterators are iterables etc. In fact, many of the capabilities of containers will be possible for such an object and you know containers are one of the hearts of python data structures.

So, to make the Student instance objects iterators, I implemented the __next__() dunder method (lines 25-32) and the __iter__() dunder method which by default should return self in lines 22-23.

Now our student objects can participate in for loops like native data structures. We can also use the ‘in’ operator on our student objects.

The last five lines of the driver code shows how I used the student object, michael, in a for loop and also used the ‘in’ operator.

This brings us to an interesting area I would like you to be aware of. Containers in python are given some defaults when it comes to dunder methods. If you look at the list of operators and their dunder methods above, you would see that the ‘in’ operator has a dunder method, __contains__() but we did not have to implement this dunder method in our Student class. This is because when we made the Student class define functionality for iterators, making it like a container class, it then by default implemented the __contains__() dunder method.

If you read through the referenced data model, you will also find other instances of defaults that some classes can have. I really cannot go on describing all the operator overloading capabilities and dunder methods that exists. It is a very long list. I would recommend you reference the data model pages which link is above if you want to find out other examples.

I hope I increased your knowledge of operator overloading and dunder methods in this post. If you want to receive regular updates like this, just subscribe to the blog.

Happy pythoning.