The pillar of modular programming in python is the module. A module, in its simplest form, is any script that has the .py extension attached to it. Each of these files has classes, functions and definitions which can be used by anyone who is using the module. Another name for modules in python programming are libraries. You must be familiar with several python libraries or modules like the os, math, numpy, matplotlib and random module because I have written articles on some of them. In this post, I will dwell on the essentials of python modules and libraries along with their benefits.

The benefits of python modules and libraries.

Imagine having to write every code yourself for any task you want to carry out if the function is not built-in. That would be time consuming, not so? Modules increase our productivity by allowing us to concentrate on the specific parts of our code which no one has written before. Since a lot of programmers are writing code all the time, we can leverage on our own productivity by being able to use their code rather than reinvent the wheel.

Also, python modules increase bug reporting. When classes, functions and definitions are defined within their namespaces in a module, you can easily isolate a bug in your code rather than bundling everything into one namespace in one file.

Modules also increases readability of code. It is easier to read a code that has fewer lines and is importing from other modules than to read a code that has so much lines that your eyes get tired. This is what modularity is about.

Getting Python modules list in your computer.

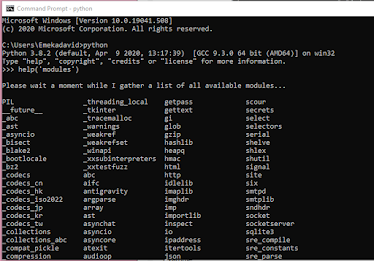

To get a listing of all the available python modules in your machine, at the python interpreter shell you can issue the command: help(‘modules’) and it will give you a list of all available python modules that are on your machine.

You would get a list such as the one from my machine whose graphic is below:

How to use modules in your own programs

For example you have a module or python library whose functions or classes you want to use. Imagine you are doing some math calculations and want to be able to use the pi definitions and sine functions and you know that a module named math has those definition and functions, how do you implement the module?

To do so, we use the import keyword. All you would have to do is to import the math module this way:

import math

Here is the syntax to import any module into your programs:

import module_name

Where module_name is the module you are importing into your program. When you import a module, python program loads the definitions from the module into the program’s namespace. In doing so, it gives you the ability to use definitions from the module in your program. For example, in the math module after importing it, I would want to use the pi definition as well as the square root definition. This is what I would do.

Notice in the program above that I used the definitions for pi and the square root function, sqrt(), that are included in the math module without having to write them myself. That is the power that modularization gives you.

Notice that in the code above, I first qualified the definitions in the module with the module name. This is to prevent name conflicts if I needed to use the same name in my program. But where you are sure there would be no name conflict, you could make it possible to use only pi or sqrt() without qualifying them by specifically importing them from the math module this way:

from math import pi, sqrt

print('Pi is:', pi)

print('The square root of 36 is:', sqrt(36))

Notice that when importing the math module I used the keyword: ‘from’ and then specifically imported only the pi and sqrt function. It enabled me to use them without qualifying these definitions.

Most times, in order to avoid ambiguity, I rather prefer qualifying definitions rather than not qualify them.

There are times when the name of the module is very long and we don’t want to be using such a long name often. Then, we can assign an alias for the module name which will serve as a short hand notation. For example, in my xml parsing program from another post, the module name was very long, so I had to alias it using a short hand of the form:

import xml.etree.ElementTree as etree

tree = etree.ElementTree(etree.fromstring(xml))

You can see that each time I wanted to use that module as qualifier, I used the shorthand rather than the complete long name. Let’s use a short hand for our math module:

Importing Modules that are not in your machine

What if a module you want to use is not already installed on your machine but you know the name of the module? Not to worry because python has a convenient way of installing modules into your machines that is easy. The program is called pip.

To import a module with module_name onto your machine, just use the following command on your terminal:

python -m pip3 install module_name

And pip will get the process running. It will even give you a report of how it is installing the said module in the background.

How to create your own modules

You can easily create your own modules with their definitions and functions. All you need to do is just write the definitions and functions in a file, name the file whatever name you wish and let the extension be .py. That’s all. That file can now be used as a module. If you want another program to use the definitions in the module, just save this file in the PYTHONPATH directory or save the file in the same directory as the program that will use it. That’s all.

Let me walk you through the process.

Supposing you wrote this cool factorial function, my_factorial(), and you want to be able to reuse them in subsequent programs. Then you could make it part of a module and name it fact_func.py. Then, save it in a directory where a program would use it. Then all you have to do is ask the program to import fact_func module and then you can use the my_factorial function.

When commands in a module should not be executed

There are times when you have written a module and you don’t want any program importing the module to have access to some definitions or functions when it is imported except when the module is used directly. For example, this might apply to some commands for testing the module. Python has a handy way for asking programs importing a module not to execute some commands. What you do is to insert those statements or commands in a separate section of the file. This section is delimited by the statement:

if __name__ == '__main__':

'''statements in this section

are not executed when the module

is imported'''

Notice how I used the if statement above to delimit the section that instructs python not to execute any statement or function in that section.

Let’s do this with examples. For example, let’s take our factorial function. After writing the factorial function, I would want to write a function that tests the factorial function to make sure it is working properly. I don’t want any other program importing this module to see this test function but I want to keep it for record purposes in case I need to make changes to the factorial function in the future, then I could do the following:

Notice that I created a separate section for testing it beginning with the if… statement above. Then ran that test at that section. When anyone imports this module, they would not be able to see the test; I wouldn’t want anyone to see it except when I am debugging or rewriting the function, or if the module is used directly and not when imported.

What are the best python modules

I often read online about the top ten python modules and libraries everyone should know. That is just a fallacy and click bait. There is no top ten. Modules are created to fill a void where one exists. You choose a module provided the definitions and functions can help you in your program. If such a module has definitions and functions that you need, then it is a module that you would use otherwise you have no business with it. So, the top module for any programmer is the module that he would use to get a task done better.

But when it comes to data science, there are some modules which do the work best you have to be aware of like matplotlib for data visualization and plotting, as well as numpy for multi-dimensional arrays and numerical programming.

So, I hope I helped increase your python knowledge with this post.

Happy pythoning.