This post is related to two previous post. First, the original post on the 0/1 knapsack problem where I explained how this can be solved using a greedy algorithm that doesn’t promise to be optimal and using a brute force algorithm that makes use of the python combinations function. After going through that post, a reader asked me to explore solving the knapsack problem using dynamic programming because the brute force algorithm might not scale to larger number of items. In the other related post which was on dynamic programming, I highlight the main features of dynamic programming using a Fibonacci sequence as example. Now, drawing on these two related posts, I want to show how one can code the knapsack problem with dynamic programming in python that can scale to very large values.

But first, you have to realize that this problem is good for a dynamic programming approach because it has both overlapping sub-problems and also optimal substructures. That is the reason why memoization would be easily applied to it.

But first, let’s start with analyzing the nature of the problem. If you read the link on the knapsack problem, I said that a burglar has a knapsack with a fixed weight and he is trying to choose what items he can steal from several items such that he would optimize on the weight of the knapsack. Now, to show you how we can do this with dynamic programming in python, I will diverge a little from the example I gave in the former post. Now, I would use a much simpler example in order to show the graphs that would help us do this dynamically.

Let’s say the burglar has 4 items to choose from: a, b, c, and d with values and weights as outlined below.

| Name | Value | Weight |

|---|---|---|

| A | 6 | 3 |

| B | 7 | 3 |

| C | 8 | 2 |

| D | 9 | 5 |

To model the choice process for the burglar, we will use an acyclic binary tree. An acyclic binary tree is a binary tree without cycles and it has a root node with each child node having at most two children nodes. The end nodes of the trees are known as leaf nodes and they have no children. For our binary tree, we will denote each branch of a node as the decision to pick an item or not to pick an item. The root node contains all the items with none picked. Then the levels of the root nodes denote the decision to pick an item, starting from the first ‘a’. The left branch denotes the decision to pick an item and the right branch the decision not to pick an item.

We create each decision node with four sets of features or a quadruple in this order:

1. The set of items that are taken for that level

2. The list of items for which a decision has not yet been made

3. The total value of the items in the set of items taken

4. The available weight or remaining space in the knapsack.

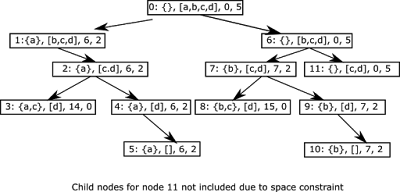

Modeling this in a binary tree we will get a tree looking like this. Each node is numbered.

You can see from the above diagram that each node has the four features outlined above in order. For Node 0, the root, the set of items that are taken are the empty set, the list of items to make a decision is all the items, the total value of items taken is 0, and the remaining space in the knapsack is 5. At the next level, when we choose item ‘a’, the quadruple changes in node 1. We chose the left branch, node 1, because the weight of item ‘a’, 3, is less than the remaining space which is 5. Choosing the left branch, item ‘a’, then reduces the available space to 2, and changes the other items for that node. The right branch to the root node is node 6 which involves the decision not to choose item ‘a’. If we decide not to choose item ‘a’ but remove it from the list, then we see that the set of items taken remain empty, the list of items has reduced to only [b,c,d], the total value of items taken is still 0 and the remaining space is still 5. We do this decision structure, making the decision to choose or not to choose an item and updating the node accordingly until we get to a leaf node.

Characteristics of a leaf node in our graph: a leaf node is a node that either has the list of items not taken to be empty, or the remaining space in knapsack to be 0. Note this because we will reflect this when writing our recursive algorithm.

Now, this problem has overlapping sub-problems and optimal substructures which are features any problem that can be solved with dynamic programming should have. We will refer to the graph above in enumerating these two facts.

Overlapping sub-problems: If you look at each level, you will notice that the list of items to be taken for each level is the same. For example in level 1 for both the left and right branch from the root node, the list of items to be taken is [b,c,d] and each node depends on the list of items to be taken as well as the remaining weight. So, if we can find a solution for the list of items to be taken at each level, and store the result (remember memoization) we could reuse this result anytime we encounter that same list of items in the recursive solution.

Optimal substructure: If you look at the graph, you can see that the solutions to nodes 3 and 4 combine to give the solution for node 2. Likewise, the solutions for nodes 8 and 9 combine to give the solutions for node 7. And each of the sub-problems have their own optimal solutions that would be combined. So, the binary tree representation has optimal substructure.

Noting that this problem has overlapping sub-problems and an optimal substructure, this will help us to now write an algorithm using memoization technique for the knapsack problem. If you want a refresher on the dynamic programming paradigm with memoization, see this blog post which I have earlier referenced.

So, we will take a pass at the code for the technique, using the 4 items outlined above. We will be using a knapsack with a weight of 5kg as the maximal capacity of the knapsack. Run the code below to see how it works. I will explain the relevant parts later.

Now let me explain the relevant parts of the code.

Lines 1 – 20: We created the items class with attributes name, value, and weight. Then a __str__() method so we can print each item that is taken.

Lines 22 – 52: This is the main code that implements the dynamic programming paradigm for the knapsack problem. The name of the function is fast_max_val and it accepts three arguments: to_consider, avail, and a dictionary, memo, which is empty by default. To_consider is the list of items that are yet to be considered or that are pending. Remember, this list is what creates our overlapping sub-problems feature along with the avail variable which refers to the weight remaining in the knapsack. The code uses a recursive technique with memoization implementing this as a decision control structure of if elif else statements. The first if statement checks to see that when we come to a node if the pair of ‘length of items to consider’ and ‘weight remaining’ are in the dictionary. If in the dictionary, memo, this tuple is stated to be the result for that node. If not, we move to the next elif statement, lines 30-31 which checks whether this is a leaf node. If this is a leaf node, then either the list of items to consider is empty or the remaining weight is zero (knapsack full), so we say the node is an empty tuple and assign it to result. Then the next elif statement considers the area of branching. Notice from the graph above that the decision tree involves a left branch (take the next item if weight is within limits) and a right branch (don’t take the next item). This elif statement considers the fact where the left branch is not approached and only the right branch. That means for that level, the right node is the optimal result for our parent node. What we do here is call the fast_max_val function recursively to check for child nodes and store the final result as tuples. Then finally, the last else statement. This considers the case where the two branches can be approached. It recursively calls the child nodes of the branches and stores the final optimal result in the variables with_val and with_to_take for the left branch and without_val and without_to_take for the right branch. Then it evaluates which of these two values has the highest value (remembering we are looking for the highest value in each parent node) and assigns that branch to the result.

After the recursion is complete for each node, it stores the result in our dictionary, before calling for any other recursion. Storing this in dictionary is to ensure that when a similar subproblem is encountered, we already have a solution to that problem, thereby reducing the recursive calls for each node.

Finally, the function returns the result as a tuple of optimal values and list of items that were taken.

Lines 55-66: This lines contains the items builder code. It builds the items and then calls the dynamic programming function. Finally when the function returns, it prints out the items that were taken for the optimal solution to the knapsack problem.

If you would like the code to look at it in-depth and maybe run it on your machine, you can download it here.

Now, the beauty of dynamic programming is that it makes recursion scale to high numbers. I want to show that this is possible with the knapsack problem.

I provide another code that implements a random items generator. The test code uses 250 items generated randomly. You can try it on higher number of random items with random values and weights.

The explanation for the codes is similar to the smaller sample above. If you want to take an in-depth look at the code for the higher number of random items, you can download it here.

Happy pythoning.