In my post on python iterators, I mentioned that one limitation of using python iterators in user defined objects is that they do not allow you to have more than one pass at the iterator when you have encountered the StopIteration exception. To conveniently overcome that limitation and give you programming power, the creators of python decided to design an object that is not only an iterable and iterator, but is also a function that yields values. That object is a python generator.

In this post, I will describe what a generator is and the advantages conferred on your programming when you use generators.

What are python generators?

Python generators are a special class of python functions that make the task of writing iterators very simple. While regular python functions will compute a value and return it, a python generator will return an iterator that returns a stream of values. To get up to speed with iterators, you can read up this post on python iterators. In regular functions you use a return statement to return a value, but in python generators you use a yield statement to indicate each element that is to be returned in a series.

The simple definition of a generator is any function that contains a yield keyword.

Let’s illustrate this with examples.

For example, take the function of computing the factors of a number.

def factors(n):

''' returns all the factors of n as a list '''

results = []

for k in range(1, n+1):

if n % k == 0:

results.append(k)

return results

In the function, factors, given a number we divide it by every number between 1 and that number. Whenever any number divides it without a remainder, that number is a factor and we store that number in the results list. At the end of the iterative division, we return the results list containing all the factors of the given number.

I want you to notice the following deficiencies of regular functions like this. 1. We had to populate the results list with all the numbers, waiting until everything was complete and then store all the values in memory. That takes up time and memory space. 2. When the function returned its results, all the variables used in the namespace of the function were garbage collected or thrown away. We can not get them again unless we call the function another time. 3. We cannot pause and resume the function if we want to.

What if we had a function that has the ability to overcome the deficiencies above and has the ability to be iterable? That is where a python generator comes in. Now, let’s use a generator to compute the factors of a number this time around. Take note of where the yield keyword is placed in the generator function.

def factors(n):

for k in range(1, n+1):

if n % k == 0:

yield k

Note that in the generator function, the return statement has been replaced by a yield statement. Also, we do not need to populate the results with all the factors like we did with the regular function but since the generator function produces an iterator that iterates through the values, we yield each of the factors as needed to the iterator. What this means is that since a python generator function produces a generator iterator, we could use the generator function in a for loop.

Take the following code as an example.

Notice that the generator function produced a gen_iterator that was itself an iterable since it implements the __iter__() and also the __next__() method. The for loop was only automatically calling on those methods and yielding the results from the generator iterator which yields the results from the generator function.

A python generator function can contain more than one yield statement and it yields the values following each yield statement in turn. Taking a cue from our generator function, we can optimize it with more than one yield statement owing to the fact that the quotient of a division of a number by a factor is also a factor, and also by testing values up to the square root of the number.

Notice that while the first iteration yielded the factors in sequential order, this second implementation although it is more optimized, did not. It just goes to show that a generator function remembers where it was in the scheme of things when it yields a result and resumes operation from where it left off. This goes to show that the big difference between a yield and a return statement is that when the return statement is executed, all variables are discarded from the function, but when the yield statement is executed, the state of execution of the generator is suspended and all local variables in the namespace is preserved. It then resumes execution from where it stopped on another invocation of the generator when the caller calls the __next__() method of the generator iterator.

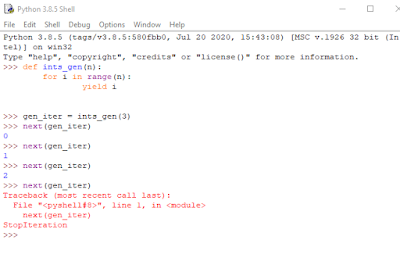

In the code example above, I asked the for loop to call the __iter__() and __next__() methods of the generator iterator automatically. I would like you to see a visual demonstration of how this works. I would use a command line invocation of a python generator function for this. For example, say we have a generator function that generates ints up to a given number. Let us see how it would be doing this with yield.

You can see from the command line screenshot above that when we called ints_gen(3) in order to yield 3 integer values, it created an iterator. We know that iterators are defined by the __next__() method. So, when we call the next function on the iterator, it yields each of the 3 integers one after the order until it gets to the end and then raises StopIteration exception which every python iterator raises on getting to the end of their iteration. This is just a simplification of how the generator function works with an intermediate generator iterator.

One thing to note too is that generator functions can also have a return statement. They do not preclude a return statement. A generator function with a return statement will raise StopIteration exception when control flow goes to the return statement, ending all processing of values.

User defined classes with generators.

According to the documentation, writing your own user defined classes that act as generators can be a messy issue. You can make a workaround by reflecting on the fact that generator functions produce iterators, and the __iter__() method also produces iterators. So, what you do is make the class you want to have a generator to be an iterable that implements the __iter__() method and let it yield its results. Here is a python generator example as a workaround.

Happy pythoning.